The Poems of Savitribai Phule: Rage, Resistance, and Rebirth

– By Shree Sauparnika V

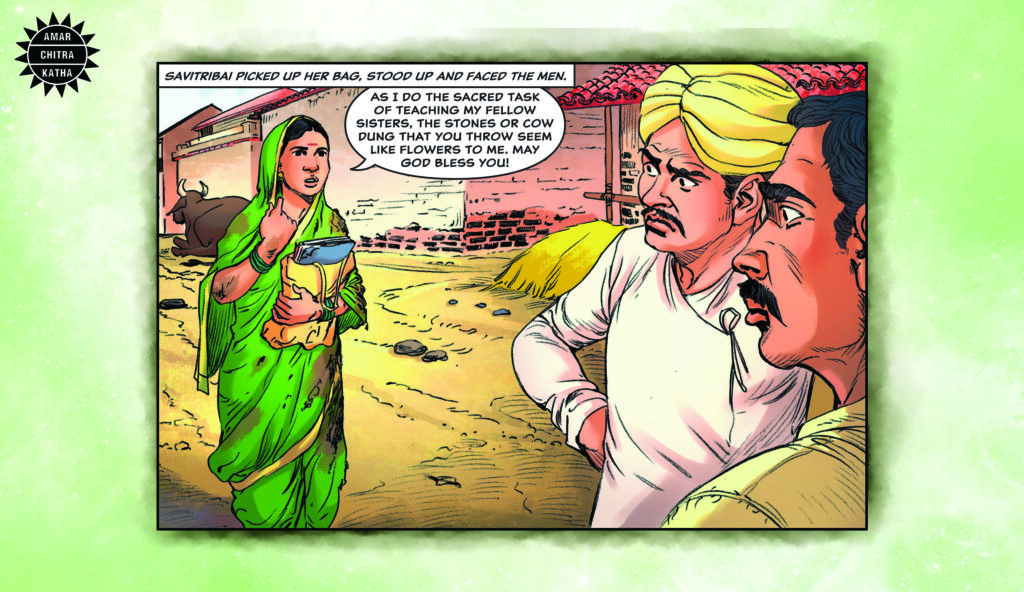

More than a century before India declared itself a democracy, Savitribai Phule was laying its moral foundation—with chalk, slate and poetry. Known to most as India’s first woman teacher, she was also a radical poet who wielded words like weapons in her fight against caste and gender oppression.

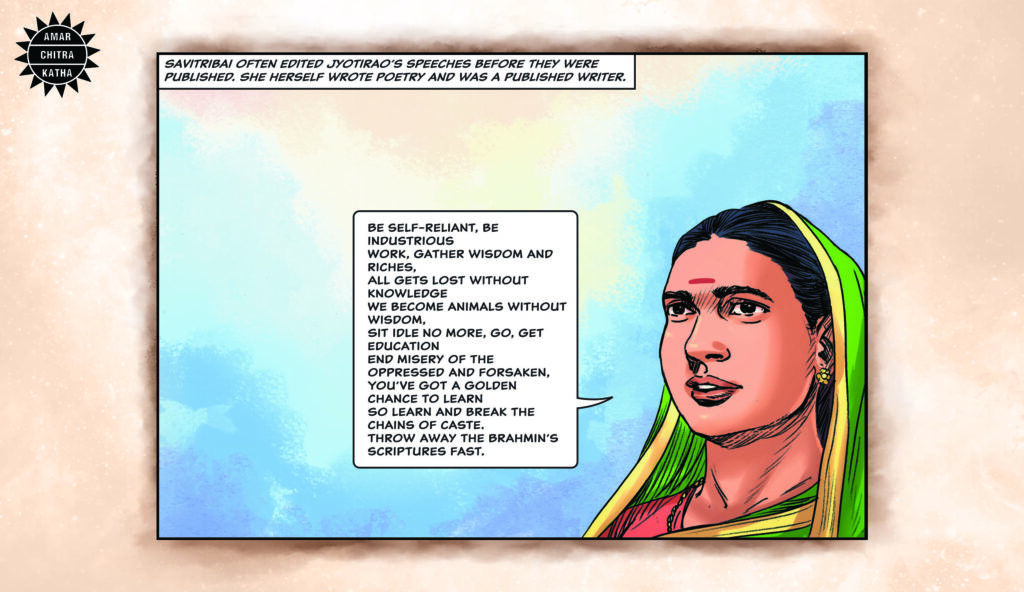

Her collection Kavya Phule, published in 1854, includes verses that cry out for justice, that imagine a better world, and that demand transformation — not just in laws or institutions, but in hearts and minds. Her poetry, written in accessible Marathi, was meant to awaken the oppressed and shake the powerful.

Today, when caste discrimination, misogyny, and social inequity still haunt the Indian landscape, her poems feel more like prophecy than relic.

Rage: Naming the Injustice

Savitribai’s poetry is known for the varying effects it has on different audiences. And it still holds true for her translated works.

“O learned man, why do you not learn to be human first?”

This is a quote directly translated from one of her poems. This sentence alone surges in depth and value when interpreted another way:

“O learned man, tell me, what is your knowledge worth

if you do not understand the pain of others?”

– Savitribai Phule First Memorial Lecture, by Prof. Meenakshi Moon

Savitribai’s rage was not veiled in metaphor — it was a searing critique of social injustice. It was rooted in lived experience—her own and that of the marginalised communities around her. She saw how religion was manipulated to maintain caste hierarchies. She called it out, fearlessly and directly. Poem after poem, she urged the oppressed to recognise their worth and reject a society that deems them inferior.

In Go, Get Education, she wrote:

“Be self-reliant, be industrious

Work — gather wisdom and riches.

All religions recognise the right to learn.

Why don’t you?”

– translated by Dr. Aalochana Gaikwad, 1994

Her anger was righteous, rooted in a love for her people and a belief in their right to dignity.

Resistance: The Pen as Protest

At a time when education was denied to women and the oppressed castes, Savitribai’s advocacy for learning was a political act. Her poetry told readers that their destiny was not bound by birth. She encouraged them to rise, to learn, and to lead.

She herself was living proof. Born into a marginalised community, she went on to become a teacher, an activist, a caregiver, and a writer. Her poems were not detached reflections — they were deeply connected to her work in schools, shelters for widows, and her resistance to social taboos.

Savitribai’s writing was not just personal expression—it was activism. She used poetry to speak directly to marginalised communities, especially Dalits and women. Her verses are filled with rallying cries to throw off the chains of oppression:

“You should become learned,

Remove the darkness within you

And march ahead, brother!”

– translated by Rosalind O’Hanlon in A Comparison Between Women and Men, 1994

In a world where women’s voices were silenced, her decision to publish poetry in Marathi, accessible to common people, was itself radical. She was not writing for elite audiences. She was writing to awaken her people.

Her resistance continues to inspire Dalit, feminist, and anti-caste writers across India today.

Rebirth: The Hope in Her Vision

Even as her poetry called out injustice, Savitribai believed in transformation—of individuals, of society, of the future. She saw education as the pathway to a new world:

“We will plant the seeds of knowledge

And nurture them with our sweat —

One day they will blossom

And the fruit will be sweet.”

– translated by Gail Omvedt, inspired by her agricultural metaphor from Kavya Phule

Her poems envisioned rebirth through awareness, collective struggle, and compassion. Her own life—educating girls, sheltering widows, adopting a child from an inter-caste family—was a living embodiment of that vision.

She was among the earliest Indian writers to articulate an egalitarian spiritual vision, rejecting orthodox religion while embracing universal human values. Her poetic vision was one of rebirth—a world where every human being could thrive with dignity.

Why We Must Read Her Today

Savitribai’s poetry is not a relic — it is a mirror and a map. It reflects the unfinished struggles of today: access to education, caste violence, gender discrimination. But it also shows us a path: to rise through knowledge, solidarity, and fearless truth-telling.

We often speak of her as a teacher, an icon, a social reformer. But we must also remember her as a poet — one who dared to write when most women weren’t allowed to read. Her poems weren’t just reactions; they were revolutions.

To read her today is to remember that change does not come from silence. It comes from voices that speak — even when the world doesn’t want to hear them.

To read her today is to believe that liberation is possible.

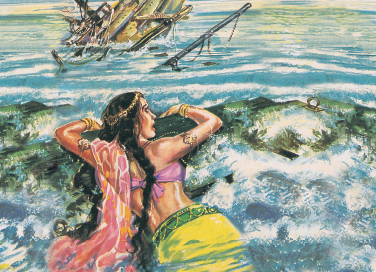

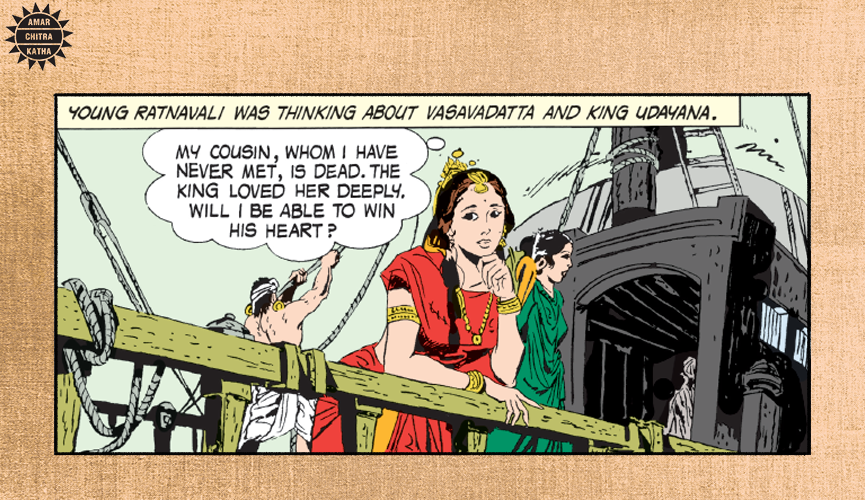

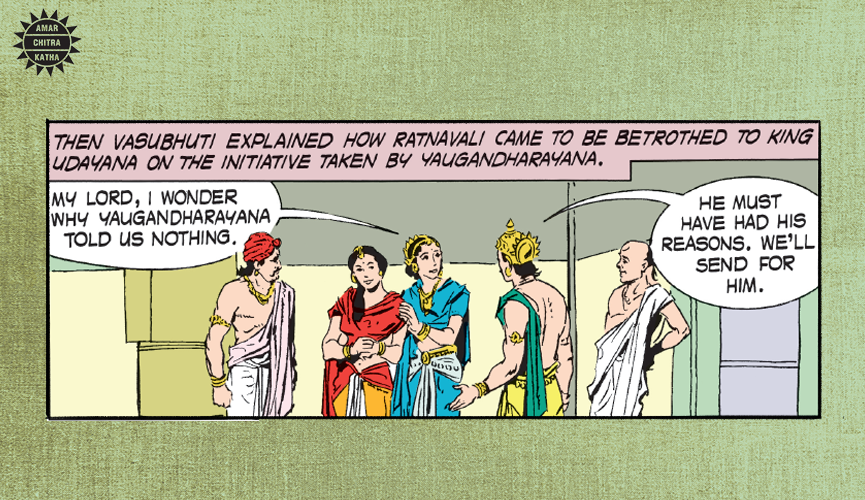

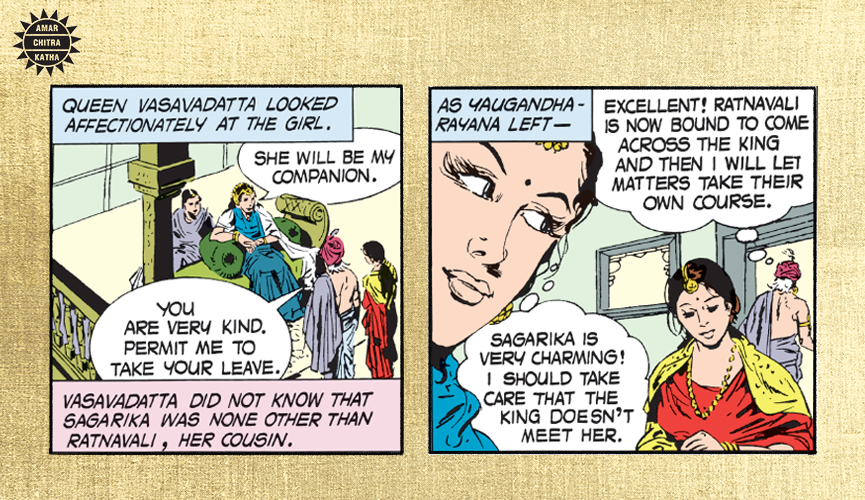

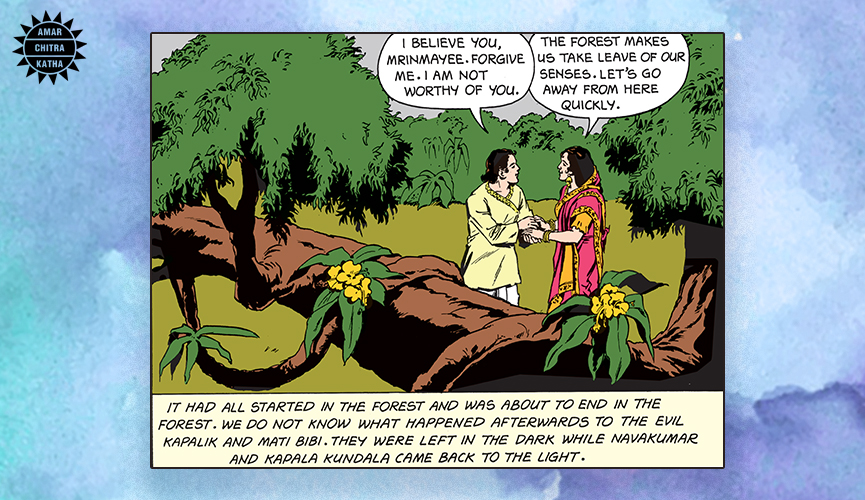

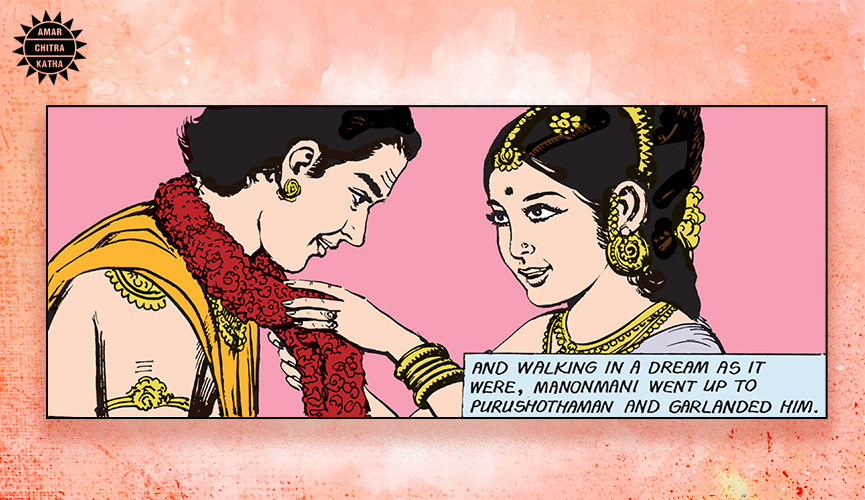

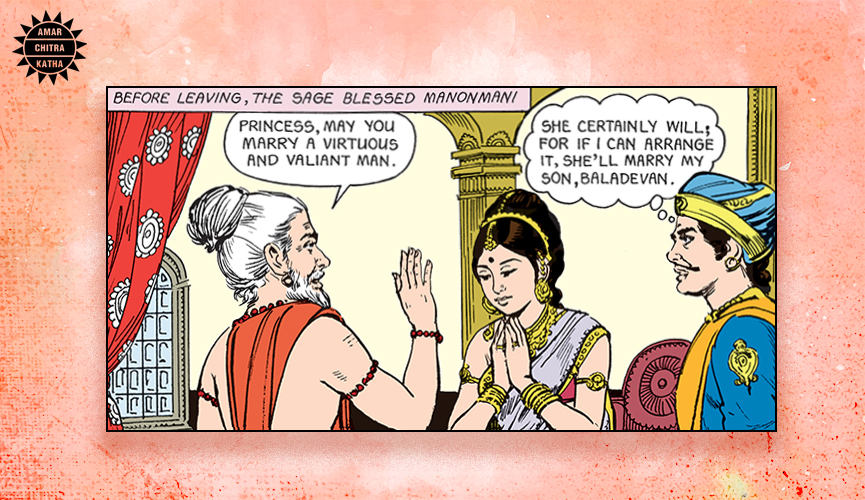

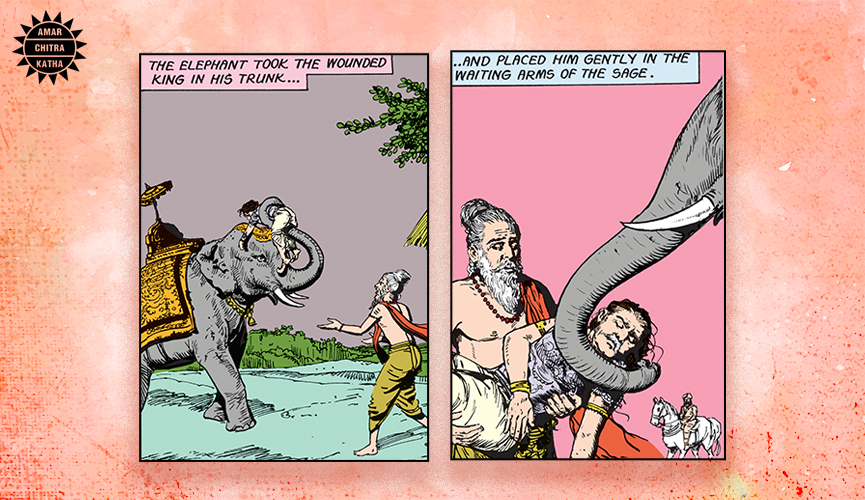

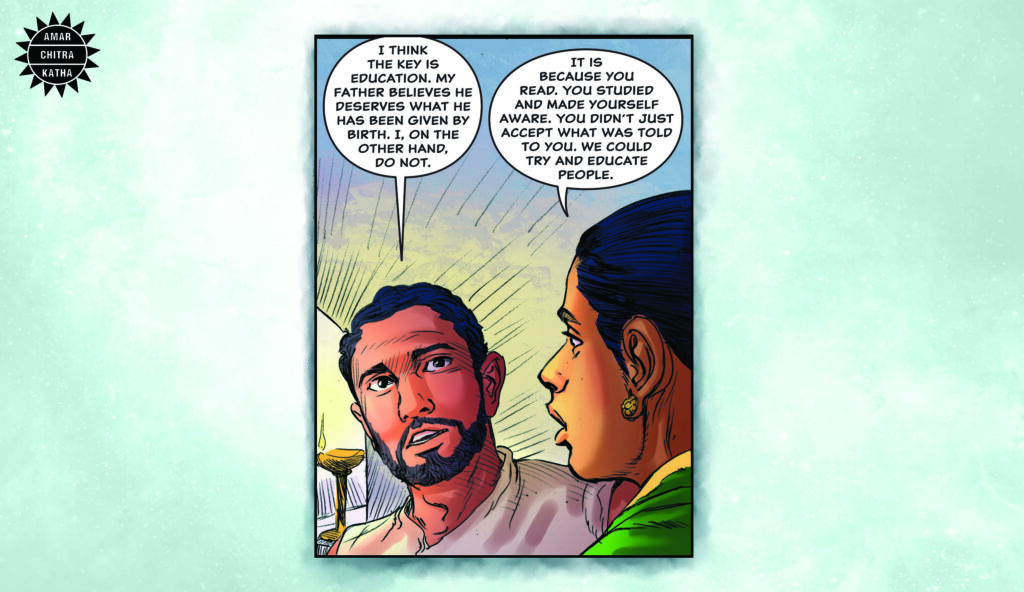

Read the incredible journey of The Phules on the ACK Comics App