By Srinidhi Murthy

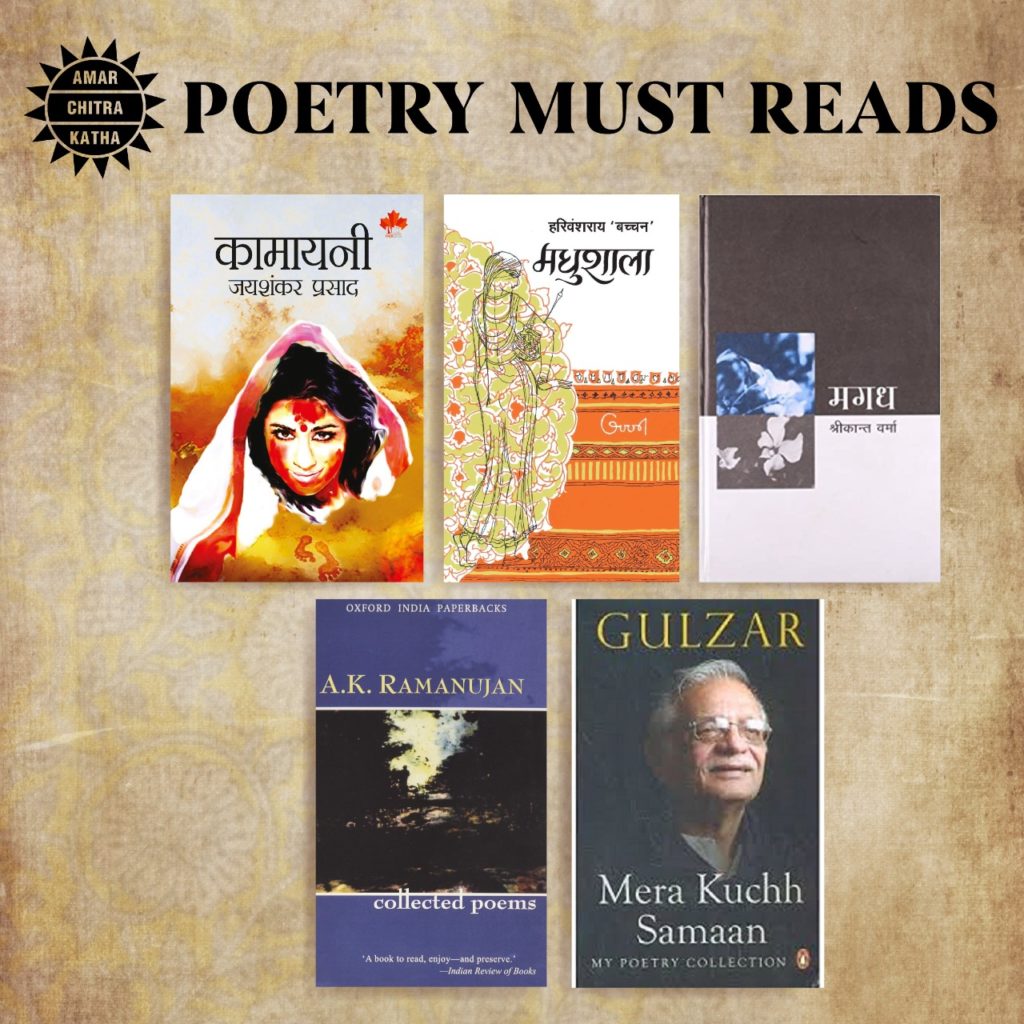

Poetry is one of the oldest forms of literature and has a rich oral and written history. Indian poetry, in particular, can be dated back to the Vedic times with Sanskrit poems crafted around more than 3000 years ago. Here is the list of must-read poetry books written by talented poets who marked their unique influences on Indian poetry in modern times.

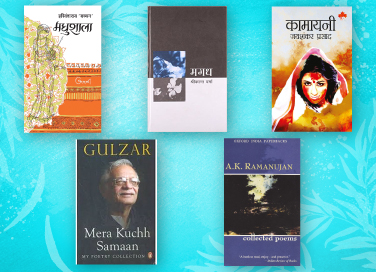

Madhushala – Harivansh Rai Bachchan (1935)

Madhushala (The House of Wine) is a famous Hindi poetry book that has 135 quatrains (i.e. a poem consisting of four lines), written by poet and writer Harivansh Rai Bachchan. The publication of this book in 1935, gave instant fame to the poet. One of the unique features of this poetry collection is that the poet ends every quatrain with the word Madhushala. In this book, Harivansh Rai Bachchan tries to explain the complexities of life with the four instruments i.e. Madhu (wine), Saaki (server), Pyaala (cup) and Madhushala. With some of his metaphorical lines, the poet also explains that the reader is the wine and he (the poet) is the cup. By filling the cup, the reader will become an alcoholic. Hence, the author concludes with this metaphor that Madhushala is incomplete without both the poet and reader. Due to its popularity, the original Hindi version has been translated into English, Malayalam, Bengali, and Marathi. The book is one of the first pieces of Hindi poetry that has been set to music with its CDs and cassettes. The poem also has been choreographed for stage performances.

Kamayani by Jaishankar Prasad (1936)

Kamayani, written in Hindi by Jaishankar Prasad, was published in 1936. Born in January 1889, Jaishankar Prasad was a novelist, poet, and playwright. In Kamayani, the poet sheds light upon the Vedic story of Manu and Shraddha, the first man and woman to survive the Pralaya (deluge) that was meant to end the world. Due to the incredible writing style of the poet, Kamayani emerges as an amalgamation of history and imagination for the reader. The book also explores the interplay of human emotions, actions, and thoughts with the help of mythological metaphors. There are fifteen sargas (cantos) mentioned in Kamayani namely faith, worry, hope, joy, lust, intellect, joy, struggle, philosophy, mystery, logic, shame, jealousy, action, and renunciation. The epic poem is considered one of the greatest Hindi literary works written in modern times.

Magadh – Shrikant Verma (1984)

Magadh, a poem written in Hindi by Shrikant Verma, was published in 1984. Considered as the crowning achievement of the poet’s life, Magadh has been established as one of the important works of Indian poetry in the late 20th century. The book consists of 56 poems written in 1979 and 1984. The poems in Magadha emerge as a reminder of the past that encounters the present and also provides the reader with a glimpse of the future. The poet Shrikant Verma presented a different style of writing in Magadh which connects the present to the history of the various historical and mythical cities. The tone of the poem is remarkably confessional and changes from nostalgic to ironic to sorrowful. Shrikant Verma was presented with the Sahitya Akademi Award posthumously for Magadh in 1987.

The Collected Poems of A.K Ramanujan – A.K.Ramanujan (1995)

A.K. Ramanujan was one of the finest English-language poets of modern India. The Collected Poems of A.K. Ramanujan was published posthumously in 1995 after the demise of the author. The book consists of the three volumes of poems published during the lifetime of the poet and also includes the fourth volume which was left unpublished at the time of his death. Some of the famous poems of A.K. Ramanujan, such as The Striders, A River, Still life, Extended Family, and Astronomer are added to the poetry collection of this book. The poems published in this book reflect the lifelong interest of the poet in structuralism, anthropology, folklore, and biculturalism.

Mera Kuch Samaan: My Poetry Collection – Gulzar (2014)

Mera Kuch Samaan: My Poetry Collection was published in English on 1 August, 2004. The book contains the selected poems of the Indian lyricist and poet, Gulzar. The book is a collection of four volumes which includes the original Hindi poems with their translated English verses. The three-hundred-page book also includes the collection of poems known as the Green Poems, which celebrates the poet’s innate connection with nature, along with the lesser-known poems hand-picked by him. The book also features hundred memorable lyrics of Gulzar along with the beautiful illustrations by the poet himself.