by Srishti Tripathi

The fan blades spin lazily overhead on a hot May afternoon, and then, a call beckons in the sun-drenched lanes, for the season’s first watermelons — all ears perk up, and make our mothers hurry out. Little hands from board games reach out and are batted away. The kitchen sounds begin. Clatter, clang!

For many of us, summers in India pulse with these simple little pleasures that have been around us forever. It is not strange to wonder then, if these luscious flavours are tied just as strongly to mythology and folklore, as to our hearts. Let’s dive then, into some of the many mythological tales and folk stories from across the country, that feature these summer treats.

Jamun: God’s Favourite

Indigenous to the subcontinent, Jamun assumes great significance in Indian mythology. It is said that Lord Rama, during his exile from Ayodhya, sustained himself on the Jamun fruit for years. His skin’s smooth texture is often likened to the fruit, and temples dedicated to him traditionally house a Jamun tree.

Lord Megha, the deity of the clouds, is believed to have descended to Earth in the form of a Jamun, explaining its dark, stormy colour, reminiscent of monsoon clouds.

The Vishnupurāna describes the universe as having seven concentric island continents, with Jambudvīpa at its centre, a region named after its massive Jamun trees. Their ripe fruit is said to create a river of rich, purple juice when they fall and burst.

Kandmool: Roots of Resilience

Kandmool are the roots, tubers, and fruits that grow naturally, in the wild. These were essential food sources for the ancient people and ascetics residing in forests. The Ramayana recounts that during their fourteen-year exile, Lord Rama, Sita, and Lakshmana frequently relied on the Kandmool they discovered in the woods. This illustrates the significance of these natural foods during challenging times and their role in sustaining life in the wilderness. Consequently, Kandmool symbolise resilience, self-sufficiency, and a profound relationship with nature. They embody the simple yet nourishing gifts of the forest, supporting those who choose a lifestyle of austerity and refrain from worldly pleasures.

Mango: The Auspicious King

Crowned the ‘king of fruits’, the Mango is associated with many Hindu deities. Kamadeva, the god of love, is often represented with a bow crafted from sugarcane, and arrows embellished with mango flowers, symbolising the sweet and enticing essence of desire. One of the most famous mango legends comes from a story involving Ganesha and Kartikeya. Once, the gods gave a divine mango to Lord Shiva and Parvati. It was no ordinary fruit—it was the fruit of knowledge and immortality. Shiva decided to give it to one of his sons but said it could not be shared. So, he set a challenge: “Whoever circles the world three times first will win the mango”. Kartikeya immediately set off on his peacock to fly around the world. Ganesha, on the other hand, calmly walked around his parents three times and said, “To me, you are the whole world”. Deeply touched, Shiva and Parvati awarded the mango to Ganesha.

Mango leaves are frequently utilised as decorative items during weddings, festivals, and other celebratory events, decorating doorways and pandals, a custom that represents good fortune and blessings. The fruit itself is presented as a sacred offering in many rituals and temples.

Jackfruit: A Symbol of Humble Luxury

With its impressive size and distinctive texture, Jackfruit also holds a special place in Indian culture. In some folk versions of the Vamana avatar story, it is believed that the demon king Mahabali offered Lord Vamana jackfruit curry along with other delicacies during the great sacrifice (yajna) where Vishnu asked for three feet of land. Because of this, jackfruit is considered a kingly fruit in Kerala and is used in Onam Sadhya (feast) to honour Mahabali.

In rural folk traditions, jackfruit trees are believed to house spirits—sometimes benevolent, sometimes mischievous. There are stories of ‘panasamma’, a tree spirit said to live in old jackfruit trees and protect the area or punish those who disrespect nature.

Though its mythological stories may not be as widely recognised, its importance stems from its connections to fertility and abundance, especially in specific regional folklore. In various Bhakti movement poems, especially in Karnataka and Bengal, saints like Kanakadasa or Lalon Fakir refer to jackfruit as the ‘poor man’s meat’, yet a gift from God. It symbolises the idea that true wealth is nature’s bounty, not gold or jewels.

Amla: Holy and Healthy

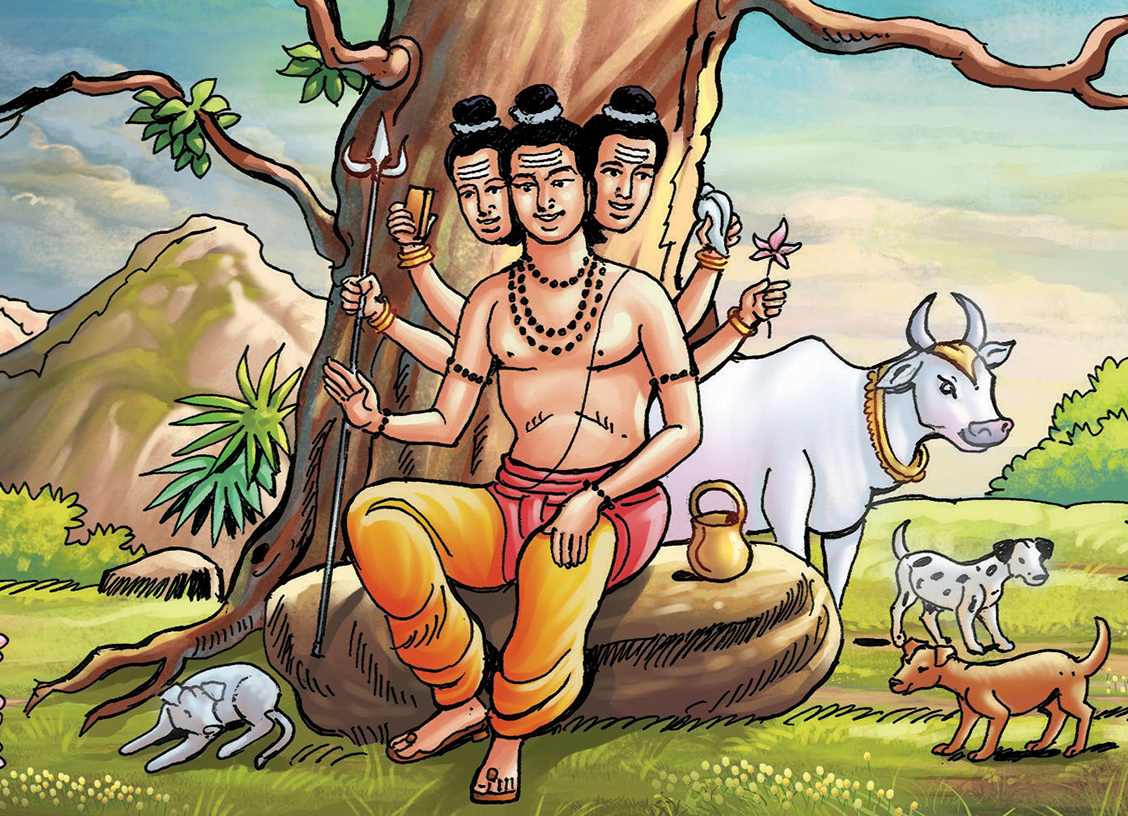

The Indian gooseberry, also known as Amla in Hindi, is said to have emerged from Lord Brahma’s tears and is considered a sacred tree. In Hindu mythology, it is believed that amla was created during the Samudra Manthan, the great churning of the ocean by the devas (gods) and asuras (demons) to obtain amrita, the nectar of immortality. Legend has it that when amrita emerged from the ocean, a few drops fell to the earth—and from these drops sprang the amla tree. This is why amla is called ‘Divyaushadhi’ or divine medicine and is believed to contain the essence of immortality.

The amla tree is also associated with Lord Vishnu. According to the Padma Purana, once, Vishnu himself manifested as an amla tree to bless his devotees; and it is said that worshipping it brings prosperity and removes impediments. The fruit is also greatly revered in Ayurveda for its therapeutic characteristics, which are thought to be important for good health and life.

Bael: Sacred to Shiva

The Bael fruit has a special place in Shaivism. Lord Shiva regards the Bael tree and its leaves, also known as Bael Patra, as immensely sacred. Its trifoliate leaves represent Shiva’s trident and three eyes. There is a story in the Shiva Purana about a poor hunter who unknowingly worshipped Lord Shiva. One night, the hunter took shelter on a Bael tree, unaware that there was a Shiva Linga at the base. To stay awake and alert while waiting for animals, he began plucking Bael leaves and dropping them to the ground—some of which landed on the Linga. At dawn, Lord Shiva appeared before the hunter and blessed him, saying that even unknowingly, he had performed a powerful act of worship by offering Bael leaves and remaining awake all night. This story is often linked to the origins of Maha Shivaratri observances. Offering Bael leaves to Lord Shiva is thought to purify the soul and is a significant aspect of Shiva worship. The fruit is occasionally utilised in ceremonies and is regarded for its therapeutic powers.

So, the next time you bite into these summer fruits, do take a moment to sit back and think about their stories. We have only touched the surface here, and we encourage you to now look them up yourself. You might just be surprised by the sweet secrets that these many summer treats carry!

To read about more myths and legends from India, download our ACK Comics App.