By Kayva Gokhale

The Indian epics – Ramayana and Mahabharata – are both fascinating studies of human behaviour. They are full of myriad characters with unique personalities and motivations, all trying to navigate through concepts like duty, honour, love, morality, loyalty and courage. Unlike a lot of other modern and ancient literature however, the epics focus equally on men as well as women, allowing both genders the same level of complexity, thus giving us some of the most well-rounded, balanced, and interesting female characters.

Women in the Epics

Often women like Sita, Savitri, Sati and Anasuya are named as ideals of purity and chastity. They are seen to be women with excellent moral fibre, women who choose death over dishonour to their husbands and families, women for whom duty and sacrifice come above all else. However, the epics also contain female characters that have shades of grey. They are intelligent, confident and duty-bound, but they also display pride, rage and thirst for revenge.

Ahalya Draupadi Kunti Tara Mandodari tatha

Panchakanya smaranityam mahapataka nashaka

This age-old Sanskrit verse is an ode to five such complex women from the epics. Literally translated, the verse means “One should forever remember the five virgins, Ahalya, Draupadi, Kunti, Mandodari and Tara, who are destroyers of great sin.”

The Virgins

At first glance, these five women don’t appear to be ‘chaste’ or ‘virgins’ in the traditional sense of the word. After all, all these women had relations with more than one man and some of them have also had to bear shame, abuse and punishment because of that. So why does this verse laud them? If these women were unchaste, then why do married women often chant this verse every day during their morning prayers?

To answer these questions, we must examine our understanding of words like ‘chaste’ or ‘virgin’. In the traditional sense, a chaste woman would refer to someone who puts her husband above all else. She is devoted to only one man, never even entertaining the thought of loving another. She obeys her husband even if that means going against her own wishes. She is ready to sacrifice everything, even her life, to this end. Sita walking through fire to prove her chastity or Savitri following Yama to win back her husband’s life, can be seen as classic examples.

However, there is another way of looking at the word ‘virgin’. A virgin could mean to be a woman who belongs to no man. She is essentially self-contained in the spiritual sense. She is a woman that no man can control or shame or ‘sully’, because she allows no one that power over herself, not even her husband. In that way, she is like the ‘pure’ spiritual ascetics, who always remain true only to themselves, dependent on no one, come what may.

Draupadi and Kunti

Ahalya, Mandodari and Tara belong to the Ramayana, while Kunti and Draupadi are from the Mahabharata. Kunti, the mother of the Pandavas, and Draupadi, their shared wife, both have massive roles to play in the way the Mahabharata plays out. Both are shown as intelligent, shrewd women with a deep understanding of the human mind. They were the guides to the Pandavas, providing advice, support and help throughout their journey, allowing them to fulfil their destiny. Both women also bear heavy burdens. They go through immense loss, sorrow and suffering but show strength and resilience that far surpasses the men around them.

Kunti, whose boon allows her to beget children from various gods, has a son, Karna, before her marriage. Her action is born out of curiosity and the courage to explore outside the bounds of traditional taboos around unmarried mothers. She is however, forced to abandon her first son – a decision that causes her much pain throughout her life. After her marriage to Pandu, she bears him three sons, all from different gods, as per his desire. She is generous enough to share her boon with Madri, Pandu’s other wife. When Pandu and Madri die, she does not crumble. She becomes the strong matriarch that her sons need and fights tooth and nail to ensure they get their rightful place in the court of Hastinapur.

Draupadi, born to avenge her father’s insult at the hands of Drona, has a life full of suffering caused by the actions of others. She is made the common wife of the Pandavas against her wishes, and faces insults about this all her life. She is staked in a game of dice like chattel by her husband, who is supposed to protect her. She is disrobed and publicly insulted in a roomful of men who watch on, unable to help her. That is where she learns not to depend on men or her husbands to protect her. She channels her rage and grief into a weapon meant to spur on her husbands in their journey. She ensures her honour is restored and assumes her rightful place as the queen of Hastinapur in the end.

Kunti and Draupadi are perfect examples of autonomous women, bound to no man. They are extraordinary in their abilities and are aware that they must shape their own destinies, rather than depend upon others. While doing so, they are more than simply wives or mothers or daughters, they are their own women.

Ahalya, Mandodari and Tara

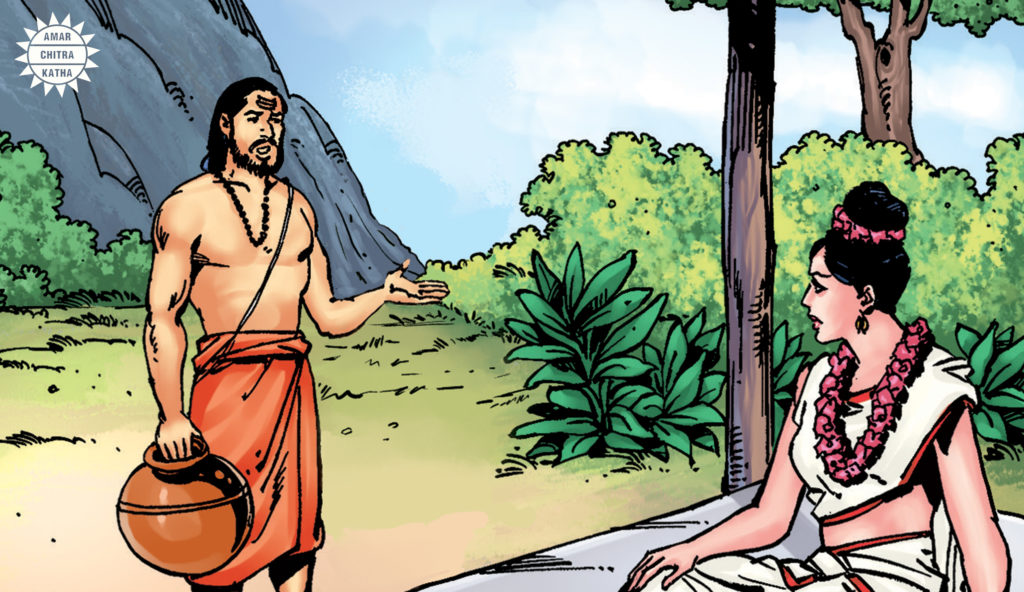

Ahalya, the beautiful wife of Sage Gautama, was cursed when she was seduced by Indra, who came to her disguised as her husband. While different versions of this story exist, most agree that she recognised Indra, but followed her instinct and curiosity and allowed herself to be seduced. Hers is a unique case of a married woman having a liaison with another man, without it being adultery or rape.

On the face of it, Ahalya can be seen as an immoral woman. But when one analyses further, one sees that she represents a primal, unbound, female energy that instinctually responds to Indra’s masculine energy. Married to an old sage, Ahalya is never given the opportunity to actualise her beauty and youth. By giving in to Indra, she allows herself to rise beyond her roles as mother and wife and becomes a lover – a woman. Throughout all, she remains true to herself, her instincts and her deepest feminine urges, making her an extraordinary woman.

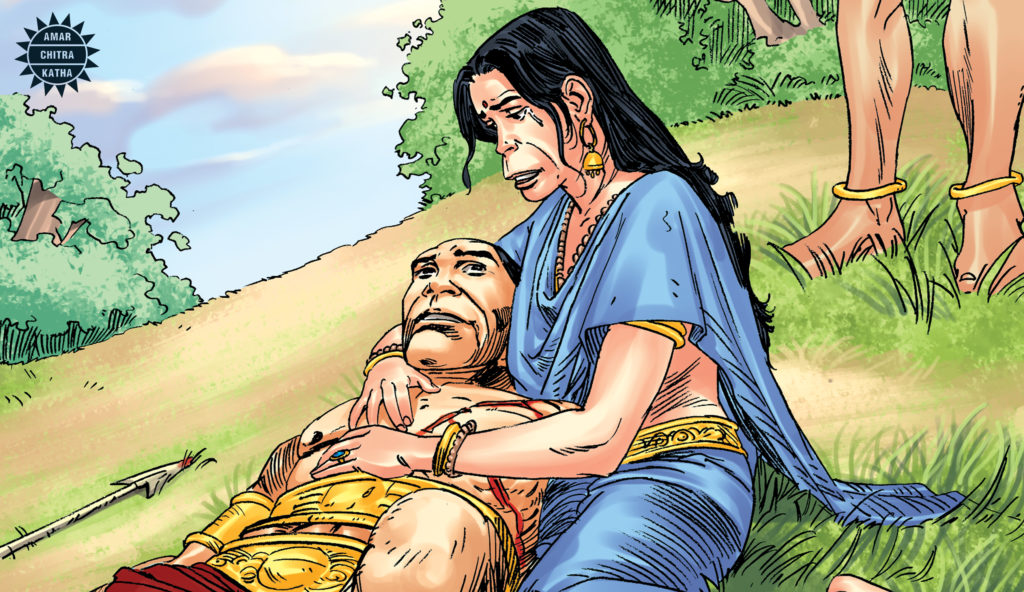

Tara, the wife of Vali and Mandodari, the wife of Ravana are similar in a lot of aspects. Both are married to strong, powerful men. However, they are confident, intelligent women who act as counsellors to their husbands, preventing tragedies and ensuring their kingdoms run smoothly. However, when their husbands don’t listen to their advice, it leads to Ravana and Vali both perishing due to Rama. Upon losing their husbands, these women don’t collapse. Tara marries her brother-in-law Sugriva, to ensure her son, Angada’s place on the throne. Mandodari marries Ravana’s youngest brother, Vibhishana, and rules by his side to keep the peace in her beloved Lanka. Tara and Mandodari are true queens. They refuse to be their husband’s shadow and do what is best for themselves and their kingdoms, showing their unparalleled determination and strength.

Panchakanya as Shakti

These five kanyas, while not chaste in the traditional sense, are true virgins in the spiritual sense. They are not bound to any man and are manifestations of feminine power. They go beyond their earthly roles of being mothers and wives and excel at being individuals, always true to themselves. While their autonomy, strength and intelligence are awe-inspiring, they also have to contend with loneliness, grief and suffering because of their extraordinary natures. Their ferocity in remaining true to their humanistic core makes these five maidens true representations of Shakti in our epics, and worthy of veneration.